B11. Discharge Planning and Follow-Up Care

These recommendations are for pediatric examiners for discharge planning, follow-up care, and referrals.

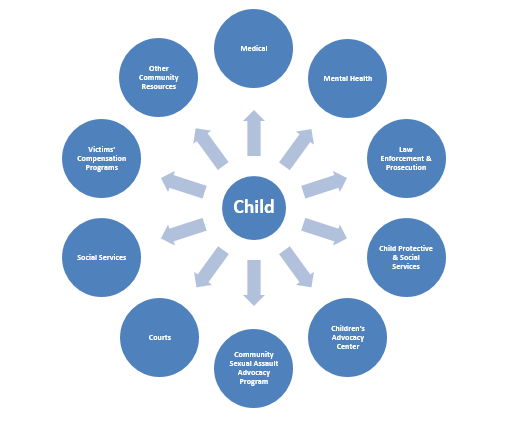

Recognize that pediatric examiners have critical tasks to accomplish prior to discharging a child, after completing all other components of sexual abuse medical forensic care. They can create a discharge plan with the child and caregiver, in conjunction with other responders in a case, for individualized community “wrap-around” services that address the child’s post-exam needs (see below for examples of potential resources). In recognition of the long-term health impact of child sexual abuse, particularly mental health consequences and the risk of acquiring HIV and other STDs, all responders should stress the importance of trauma-informed counseling and other supportive services as essential components of follow-up interventions, including the need for follow-up medical testing and care (adapted from Day & Pierce-Weeks, 2013).

Connecting Children to Community Resources

Use tailored discharge forms and material. These forms should be inclusive of the unique needs of prepubescent children who have received sexual abuse medical forensic care. They can help examiners in verbally summarizing for the child and caregiver: the care provided, tests completed, medication provided/prescribed, follow-up testing and care scheduled, and entities involved in these cases. They can also guide in explaining common reactions of children to sexual abuse, helpful caregiver responses, and follow-up services. Those developing these forms and materials should strive to make them culturally inclusive, tailored to children’s communication capacities, and linguistically appropriate for children and caregivers (likely necessitating the need for multiple formats). Use of standardized forms and materials can help examiners maintain the focus on health issues during discharge planning.

See www.SAFEta.org for sample discharge forms and materials.

Address the child’s physical comfort needs before discharge. (See A1. Principles of Care) These needs differ from one child to the next, but might include: allowing them to wash and brush their teeth, providing replacement clothing if their clothing was collected as evidence, assisting them with dressing (depending on their age and the availability of a caregiver), ensuring they receive a snack and drink if they are hungry and thirsty, etc.

Facilitate discharge planning with the child and caregiver.[1] If the child assents, it may be helpful if the examiner also invites other responders involved in the medical forensic exam process to participate in this “exit conference,” depending upon their availability and specific case needs: e.g., victim advocate(s) who have accompanied the child and caregiver through the examination; a hospital child life specialist or social worker; a mental health provider who counseled the child and/or caregiver or who will provide future services; or other medical specialists that were or need to be involved (e.g., infectious disease or surgery).

|

Address the following health and related issues during discharge: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

o IDENTIFY RESPONDERS WHO CAN PROVIDE SAFETY PLANNING ASSISTANCE (e.g., a victim advocate, children’s advocacy center staff, victim service specialist, a hospital social worker, child protective service worker, and/or investigators). Immediately involve law enforcement and/or child protective services if there are imminent physical safety risks—communicate this urgent need in the oral mandatory report of abuse or via another call to them. Children with immediate safety risks should not leave the health care facility until these concerns are adequately addressed. o CONSIDER SAFETY ISSUES AND SCENARIOS. For example: Will living arrangements or other environments the child and/or family frequents (e.g., home, school, after-school activities, child care, church, neighborhood, or peer group) expose them to threats of continued violence? Will the perpetrator have access to them in such settings? Is there a need for emergency shelter or alternative housing options/out-of-home placement? Are the child and family eligible for protection orders? Is there a need for enhanced security measures at home? If the child or family feel unsafe, what will they do to obtain help? Is there a potential for backlash against a child and family for their lack of silence about the sexual abuse (e.g., if a powerful and respected family member or member of the community has been named as the suspected perpetrator)? If a child or caregivers with physical disabilities require temporary shelter, is the shelter accessible and are the staff able to meet their needs for personal assistance with activities of daily living (adapted from Nosek & Howland, 1998)? What if it is known or suspected that images of the abuse are available online or have been shared electronically? What are the safety issues and strategies to address them? If it is inadvertently revealed to family members that a child victim is gay or transgender, what can be done to minimize the impact of the family’s reactions to this revelation on the child’s healing from the sexual abuse? (With all of these questions, discuss options, and help the child and caregiver develop a plan for physical and emotional safety) Note safety planning tips and forms can be helpful; however, safety planning assistance itself should be tailored to an individual child/family’s situation and plans should be re-evaluated if circumstances change.[8] |

|

|

Note that follow-up medical testing and care might include (depending upon case specifics):

· Medical follow-up treatment for health concerns identified at the examination;

· STD follow-up testing and treatment, including for HIV (see B10. Sexually Transmitted Disease Evaluation and Care); and/or

· A short-term follow-up examination for children who had acute injuries/trauma (including surgical cases) to document the development of visible findings and photograph areas of injury, and then an examination 2 to 4 weeks later to document resolution of findings or healing of injuries (follow jurisdictional policies for describing indications and procedures for follow-up for documentation purposes).

To the extent possible, schedule medical follow-up appointments prior to discharge. The examiner, child, and/or caregiver should determine the most appropriate provider/location for each appointment (e.g., the primary care provider, return to the exam facility, specialty care provider, or a community clinic).

Partner with other responders to aid the child and/or caregiver in overcoming roadblocks to receiving follow-up health services. For example, examiners can connect the caregiver to a victim advocate or social worker to assist with transportation to and from appointments and out-of-pocket medical costs, or a mental health provider to discuss family dynamics that may impede necessary care (e.g., the child’s siblings are blaming her/him for “breaking up the family” and pressuring the child to say she/he lied about the abuse).

When making referrals for services, examiners must take into consideration the resources available to the community and confidentiality issues. It would be problematic, for example, if the follow-up health care options were hours away from the child’s home or if the child’s family had a conflict of interest with the one mental health counselor in their small, rural community who had expertise in working with child sexual abuse victims. Examiners, in conjunction with the multidisciplinary response team, need to think creatively about how best to overcome resources and confidentiality challenges to ensure that children and their families have access to the follow-up care and services they need. (See A3. Coordinated Team Approach)

| Table of Contents | Glossary and Acronyms |

[1] This section was drawn in part from Jones and Farst (2011).

[2] Examiners may make statements to reassure children and caregivers about the child’s health, such as “your body is healthy” or “lack of injury does not mean an assault did not occur,” but they should avoid wording that could have legal implications, such as “no evidence of abuse was seen today” or the child looked “normal.”

[3] A psychosocial assessment may occur after the medical forensic examination, perhaps conducted by children’s protective services, a children’s advocacy center, or other victim advocacy program. The International Rescue Committee (2012) offers a psychosocial assessment tool for children who have been sexually abused.

[4] As referenced earlier, CrimeSolutions.gov at www.crimesolutions.gov/PracticeDetails.aspx?ID=45 offers a discussion of therapeutic approaches for children who have been sexually abused and their families. Also see the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center’s Child Physical and Sexual Abuse: Guidelines for Treatment (Saunders, Berliner, & Hanson, 2003) at https://mainweb-v.musc.edu/vawprevention/general/saunders.pdf. The Child Welfare Information Gateway at www.childwelfare.gov/topics/responding/trauma/treatment/ provides links to resources on the treatment programs to meet the needs of children, youth, and families affected by trauma.

[5] A few examples of studies that speak to this association: Dong et al. (2003), El-Sheikh and Flanagan (2001), and Fitzgerald et al. (2008).). More generally, see adverse childhood experience (ACE) studies www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/index.html.

[6] It can be challenging to identify mental health providers who not only have expertise in treating child sexual abuse victims and/or their families, but also who are known to appropriately and respectfully work with specific populations of children. Multidisciplinary response teams in specific communities are encouraged to consider these challenges in advance and partner with those serving diverse populations to identity “best case” mental health referrals for specific populations and to have contingency plans in place. (For example, consider the best alternative if a community lacks a mental health provider who has experience in gender identity issues and child sexual abuse.)

[7] As for roles and services, the child and caregiver should be informed about the following: if there is a local children’s advocacy center, its services and coordination role; investigative processes in criminal justice and child protection systems (as appropriate to the case), assistance available from those agencies, and when and how to contact investigators; child protective services to assist children with safety issues in the home; mental health counseling options for child sexual abuse victims and their families; victim advocacy—the range of services and options in the community; financial resources available to help cover medical and other costs associated with victimization, and assistance available for completing financial aid applications; and other community resources that might be applicable in a particular case (e.g., local HIV services).

[8] Some related resources: Stop it NOW! (2008, n.d.) through www.stopitnow.org/help-guidance/prevention-tools offers tip sheets related to family safety planning to protect children from sexual abuse, in general and specific to children with disabilities. The West Virginia Foundation on Rape Information and Services (2012), through its Sexual Assault Services Training Academy at www.fris.org/OnlineTraining/SASTA.html, offers safety planning material and a related online course for service providers working with victims of sexual violence.

[9] For example, see the parent tip sheets offered in Yamamoto (2015).